Lucas Schaefer teaches at a girls’ school in Texas.

A few weeks ago, one of my 8th graders interrupted our weekly current events round-up to ask the meaning of the word filibuster. If you find it maddening that most major legislation now requires a supermajority to pass in the Senate, imagine the indignation of a group of 13-year-olds who had just been subjected to months of studying the Constitution suddenly learning that 51-49 is actually a losing proposition. Earlier in the year, we’d watched the Schoolhouse Rocks video, I’m Just A Bill, and my girls are well-acquainted with checks and balances, separation of powers and the like. Increasingly, though, the singing parchment dancing on the steps of the Capitol feels like an artifact rather than a well-intended, if naïve, blueprint for how laws get passed in Washington. By the end of our detour into the intricacies of the F-word (as we’ve started calling the procedural manuever) the girls had raised a valid question: If you can just mess with the rules, what’s the point of learning all this stuff, anyway?

Middle school is the perfect time to study politics. After all, politics allows kids to confirm all of their suspicions about the hypocrisy and mendacity of us adults. By the time they’re twelve or thirteen, kids already know that what we say and what we mean isn’t always the same thing. They’re well aware that “grown-ups” often have no idea what they’re talking about, even though we’ll frequently pretend that we do. Thirteen-year-old girls have some of the strongest BS detectors on the planet, and in studying politics, they get to use them.

As a result, the students’ political analysis is often considerably more astute than that of the pundits, some of whom the girls have already encountered and seem to regard with deep and appropriate suspicion. In discussing the filibuster, for example, the girls’ first question was why the Democrats had done nothing to reform the system, even though they’re the ones in power. It didn’t take them long to figure out why Harry Reid might be inclined to maintain the status quo. Earlier in the school year, during the Republican convention, the media stumbled over itself to praise Ann Romney’s convention speech, while the girls were unenthused, especially after Mrs. Romney inexplicably yelled out “I love you women!”, which they seemed to regard as a pander, and a super weird one at that.

While middle schoolers may have always been natural skeptics, the internet has allowed them to gauge the accuracy of their BS thermometers in ways they couldn’t before. During current events, my students bring in articles from traditional newspapers, but also from fact-checking websites like PolitiFact or the Washington Post’s Fact Checker, which rates the truthfulness of politicians’ statements on a scale of Pinocchios. During the election, one student informed the others that according to her research, “Obama lies more frequently but Romney’s lies are much bigger.” Other students have read up on the media’s tendency to create “false balance” or false equivalencies between the two parties in an effort to appear “fair.” In short, kids have gone from suspecting politicians and pundits bend the truth to knowing for sure.

Of course, if politics appeals to the students’ burgeoning skepticism about the world around them, it also allows them to observe change in a way that gives them hope. They like debating the issues of the day, and they revel in the possibility that their own ideas might persuade others. I started teaching just after the 2008 election, and my students at the time repeatedly brought up the importance of young people in that race, excitedly noting that some kids may have persuaded their parents to vote for Obama. Last month, all of my 8th graders wrote to Congress about issues that they care about, and their final letters were thoughtful and personal. One wrote in favor of the DREAM Act, another detailed her grandfather’s use of medical marijuana to cope with chronic illness. A girl I’ll call Samantha sent a detailed letter in support of gun control to her local representative. She was skeptical he’d have much to say about it (thanks to her web research, she already knew he had an A+ rating from the NRA). Still, there was much excitement when he actually wrote back.

His letter was cordial but evasive and ended with a promise to keep Samantha’s ideas in mind when he has to vote on legislation. At first, Samantha seemed dejected by what appeared to be a form letter (near the end, the Congressman encouraged her to continue on with Girl Scouts, despite the fact that she wasn’t one and hadn’t mentioned scouting in her letter). But the idea that an elected official had read one of the girls’ words and actually wrote back pleased everyone. The students inspected his words so carefully that eventually Samantha ran up to the office to make copies for the whole class.

I recently asked my students to write down the bits of our civics work that stuck with them. “Lots of people tend to be loyal to their party instead of what they believe,” wrote one. “Gallup polls are not always accurate,” wrote another. One student offered bullet points under a variety of categories including “What I Remember” (“social security is a political minefield”) and “What Made No Sense” (“Electoral college: I understand it but I think it’s ridiculous”). Others mentioned the issues they cared most about: immigration, education, gay rights. One simply wrote, “I now know what I don’t want to be when I grow up.”

In later conversations, many of the girls expressed disappointment that I wasn’t able to find my own 1992 “election journal” from 5th grade, which I’d mentioned at the start of the year before assigning a similar, 2012 version of the project. The students wanted to know if the issues were the same then as now, if the players had changed. (The first time I projected a picture of Bill Clinton in my class this year, a student raised her hand and asked, “Isn’t that Hillary’s husband?”) I told them what I could remember from the journal: an entry on the “ozone layer,” a funny picture I’d cut out and included of an animated Ross Perot. The girls wanted to know if politics has always been so petty and stagnant. (“I am curious as to why Republicans and Democrats have remained prominent for so long,” one student wrote in a reflection. “It seems like so many other aspects of society fluctuate but those haven’t changed”). Politics has always been messy, I assured them. Partisanship and dysfunction aren’t unique to this time.

The particular dysfunction of our current politics, however, does give me pause, because it’s coupled with a generation of students who are tech-savvy, media-savvy, and uncomfortably self-aware. I’m impressed with the deep skepticism with which my girls approach the world around them, with the way they’re hyper-attuned to platitudes and insincerity. But I also hope they hold on to the passion they felt writing their letters and the excitement they felt when one came back. I hope their skepticism doesn’t morph into cynicism. We study how our country is supposed to work, even when it isn’t working, so we can struggle toward an ideal. I hope the system doesn’t seem so broken that my students come to see that struggle as pointless.

For the most part, of course, these worries are not new. Attempting to stay true to an ideal in the face of an encroaching “real world” is the basis for much of our literature, after all. Throughout American history, we’ve had politicians who changed the rules and behaved like children. The difference now, for better or worse, is that the actual children have the skills and tools to notice.

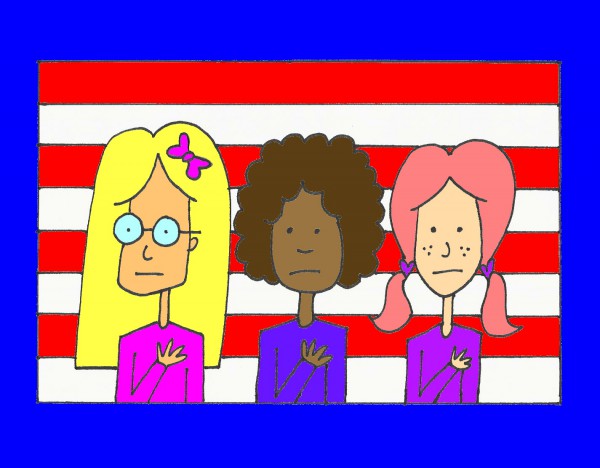

Illustration by Graham Gremore. Graham Gremore is a writer and cartoonist born and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing, and he is the co-founder and co-director of StoryFarm, a literary arts non-profit in San Francisco. His cartoons have garnered over 125,000 views on Youtube, and have been featured on websites including HuffingtonPost and BuzzFeed. Visit him online at www.grahamgremore.com.