I remember the first customs card I ever filled out. I was thirteen, and my family had just spent three months in Australia, where my dad had been working. (Little did I know at the time about my future in that country.) On the plane home, over the Pacific, flight attendants clipped down the aisles, all business and repetitive smiles, passing out blue and white cards. “Customs declaration?” they asked, and it was the kind of ask that is really a tell, because you have no choice but to fill out the card. I read it carefully, fascinated and intimidated. Its questions made me think back through our trip—was I bringing any fruits, seeds, or animal products with me? I didn’t think so…but then, what about the shells I had found on the beach, or the hat-shaped gumnuts that pebbled the ground, which I now carried as good-luck-charms? Would I even know it if I was carrying disease agents or cell cultures? How close is “close proximity to livestock,” and did walking near a horse a couple of months ago count? I knew I wasn’t carrying more than $10,000 cash, but I was less sure whether any of the merchandise I was carrying could be considered “commercial,” because after all, I had bought it at stores, and wasn’t that commerce?

I spent half an hour tallying up the “value of all goods I had purchased/acquired abroad,” and I had to ask for a second form because I kept crossing things out, second-guessing myself, feeling less sure of my reading comprehension skills, and increasingly sure that I would get in trouble for bringing something illicit into the country that I didn’t even know was not allowed. I was the kind of child (and now, the kind of adult) who over-thinks things. In the end, they didn’t even look at my form, because I was with my mom, and they only want “one per family.” In fact, the first question on the form, after your name and date of birth, asks for the “number of family members travelling with you.” This is perhaps not a very complicated request when parents are travelling with children. But it begs the question: who counts as family?

I suppose the adage that “friends are the family we choose for ourselves” is not a compelling argument for the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol. What about step-siblings or cousins travelling together? A couple who have been dating six months? An unmarried couple who have been together ten years? A just-married couple? A man and his mail-order bride? I didn’t think about any of these questions then, although I would scrutinize them to death years later. But for now, my point is this: for a form that more than a million people are required to fill out each day, the U.S. Customs Declaration is remarkably complicated. And it makes even law-abiding citizens feel like they have done something wrong.

Couple that with the questions one is likely to be asked by immigration officials when entering the United States, and it’s enough to put anyone on high alert. What was the purpose of your visit? How long have you been away? Did you visit any countries other than the one you have just come from? All of a sudden, your heart is beating faster, and you hope the officer can’t see the sweat beading on your back. When the dated rubber stamp makes its satisfying contact with your passport, and the officer says “Welcome home,” usually without a hint of welcome in his voice, you realize that you haven’t breathed for maybe the last two minutes and you are flooded with a sense of not just relief, but the feeling that you have gotten away with something. You are one of the lucky ones—you have been let into America.

Or, at least, that’s how it always feels to me.

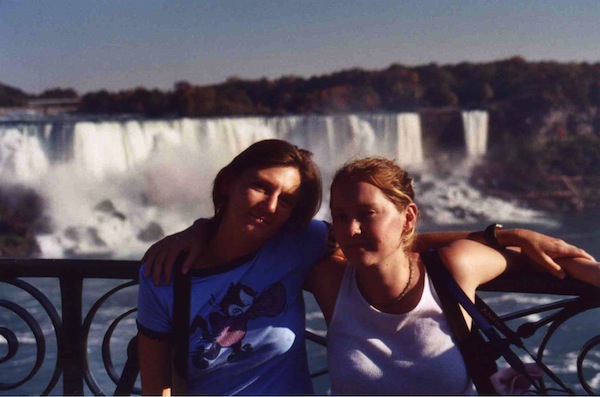

So now, fast forward eight years from my terrifying first encounter with entering the United States. In the interim I have gone to college, taken a few more international trips, and become adept at the mindfulness required to not hyperventilate while interacting with immigration officers—but I have never crossed an American border with a non-U.S. citizen before. I am twenty-one and in love and driving with my Australian girlfriend to the Honeymoon Capital of the World: Niagara Falls.

We are not going there for our honeymoon, though. Nor are we going to gape with wonder at the six million cubic feet of water gushing over the 188-foot drop into the Niagara Gorge every minute, nor don disposable ponchos and ride the Maid of the Mist into the prismatic, roaring spray. Jodi’s visa is on the verge of expiry, and we are in search of New York City’s nearest international border. It’s October, we’ve been dating for two months, and Jodi is living with me not-quite-legally in the dorm room provided by my job as an R.A. for college students experiencing a semester in the Big Apple. We sleep in a single bed and our lives look like some disheveled, lesbian version of a Nora Ephron rom-com—nights riding the elevators to the observation deck of the Empire State building, days sticky with Coney Island sugar and the salt of the sea. Walks down the Brooklyn Heights promenade, just a few minutes from our illicit residence, where the view of the World Trade Center is as conspicuously absent as missing teeth. Lots of photos taken at arm’s length, so close up you can’t see the background, but you can see that we are happier than we have ever been. It’s October. Her flight home is in December (what then? we have no idea), but first things first: her visa expires next week.

Faced with an expiring visa, she can do one of three things: A) she can stay in the U.S. anyway, becoming, overnight, a dreaded “illegal alien”; B) she can go home to Australia; or C) she can go to any other country that will let her in. Think Uncle Sam as curmudgeonly bartender: you don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here. And if you do stay here, we’re going to turn off all the lights and stop serving drinks, so it’s not going to be very much fun for you. Hence: Canada, the gleaming beacon of hope for those oppressed in America since its founding—escaped slaves, draft dodgers, and, more recently, gay couples wanting to get married have all looked to the North Star.

I don’t pretend that our case is as dire as that of the former examples. And we aren’t going to Canada for Canada; we’re going because it’s not America, and all Jodi has to do in order to re-start her visa clock is, essentially, set foot outside the U.S. Not that it’s that simple, as time will tell. But we have no choice; we want to avoid A at all costs, and, being young and in love we cannot fathom the separation of B, and so we choose C: renting the cheapest compact car we can find, and driving, if not to the ends of the earth, then to a place where the world falls away at six million cubic feet per minute into an unfathomable chasm, which we will cross over, knowing it will either destroy us or wash us clean.