Kyle Thompson was terrified when he got arrested last spring for allegedly assaulting his biology teacher. It wasn’t just the realization that he had ended up in a place—the Farmington Hills, Michigan police department—where he felt like he didn’t belong.

“I was real scared, especially because I saw my mom come in there and I thought she was going to be real mad at me.”

Kyle was 14 when this happened, a freshman at a high school in suburban Detroit. He’s too young to drive. Still has braces on his teeth. And he’s as afraid of his mother as he is of the cops. In other words, he’s a kid.

I’m working on a story about Kyle and school discipline for Life of the Law, so tune in next week to find out how he ended up being taken out of his school in handcuffs, and what’s happened to him since. But I don’t think I’m spoiling anything to say that he’s an example of the growing number of kids ending up in the criminal justice system for seemingly minor infractions at school.

Law, of course, is open to all kinds of interpretation—that’s what lawyers do, right?—and the same goes for school rules. So what I call disagreeing with the teacher, you might call insubordination. Or what you call a shoving match, I might call assault. The problem is that schools have been coming down hard on the criminal justice interpretations. And, if you look at the data, they’ve been coming down especially hard on African-American boys and students with disabilities.

It’s gotten so bad, in fact, that earlier this month, the Obama administration issued a 35-page document outlining appropriate alternative methods for school discipline. As Attorney General Eric Holder said when he announced the new guidelines, “A routine school disciplinary infraction should land a student in the principal’s office, not in a police precinct.”

In the last 20 years, more and more districts have put police into schools, to protect students, teachers, and administrators. But in a lot of places, more police has translated into more student arrests, usually for relatively minor infractions. Zero tolerance policies, which a lot of schools enacted starting in the 1990s, made it easier for police to do that, and harder for administrators to make what amount to judgment calls.

While I was reporting my story about Kyle, I spoke to Steven Teske, who is a juvenile judge in Clayton County, Georgia. When he realized how many of the cases coming into his courtroom were silly, school-based misdemeanors, he set about changing the whole way his county deals with school discipline. The way he put it was, “Really what this comes down to is, is this a student who scares me, or is this a student who makes me mad?”

The district basically decided that most misdemeanors on school grounds would not be referred to the criminal justice system (at least not the first offense). Almost immediately, the number of students ending up in his courtroom dropped.

There’s another side to the story, of course. Teske describes how arrests actually increased when budget cuts forced his district to get rid of officers in middle schools. When kids got in trouble and outside cops came in to deal with the problem, they were more likely to arrest kids.

And when you hear stories like Newtown—or the less spectacular though thoroughly horrifying stories of smaller scale shootings—it’s easy to understand why police should be protecting our schools. But it’s also in all of our best interests to keep kids—especially vulnerable ones—in school and out of the criminal justice system.

So what do we do? Tune in to the latest episode of our podcast on Tuesday for more.

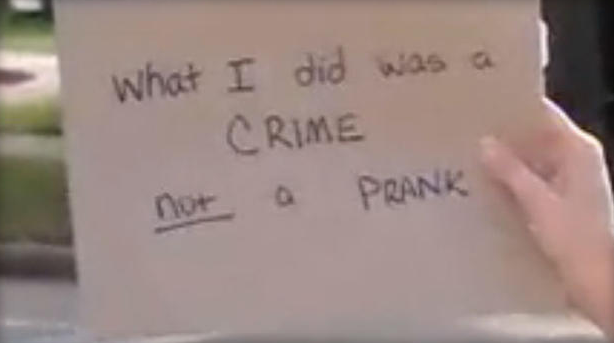

Photo: As part of a plea deal, eleven Texas students charged with burglary as part of a senior prank were ordered to stand outside Clements High School wearing signs. CBS News

Alisa Roth is a reporter and an editor for Life of the Law.