Erica Barth grew up in Philadelphia. Most of the time when her family drove into New York City, they took the Lincoln Tunnel. But every now and then they would drive over the George Washington Bridge, and when they did, her dad would ask, “Everybody ready?”

That’s when they would sing the song.

“It was a ridiculous song,” she explains. “But I always just thought it was a real song, like from a musical or something.”

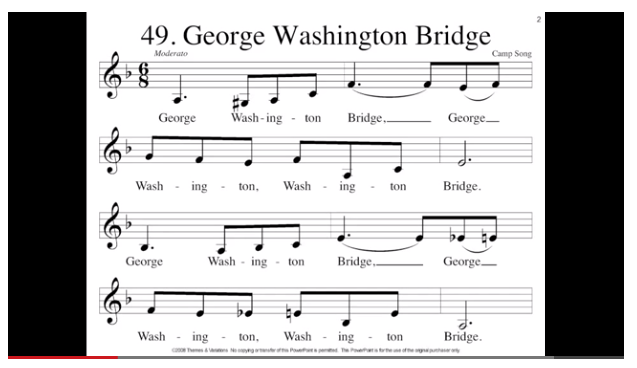

The song was a simple one. The lyrics repeat, “George Washington Bridge!” with escalating notes and changing emphasis. But the family knows it well, and they still sing it whenever they go over the bridge. Recently, Erica and her sister were driving over the bridge and sent their father a video of them teaching it to his grandchildren, Erica’s niece and nephew.

The song has become so ingrained that none of the Barth’s feels like they can drive over the bridge without singing it.

“I’m sure I’ve sung it to adult passengers without a second thought,” says Larry Barth, a lawyer and Philadelphia resident.

Erica, who now lives in New York and runs The Harlem Yoga studio agrees. “I sang the song randomly to some friends about a year ago,” she says, “and they were all like, `That’s not a real song!’ and I was like, `Yes it is!'”

But she didn’t know where it had come from, so she looked it up. A rudimentary search came up with nothing, so she asked her dad if it was a real song.

He answered, “I think I made it up to entertain you guys on road trips.”

Now, this is where the story gets weird. Erica believed that the song was made up by her father, who passed it on to his children, who were now passing it on to the next generation. But then one of those friends from the car ride sent Erica this, a YouTube video of a family claiming THEIR grandfather had written a song almost identical to the one Erica father had “written”:

Stranger, still, was that on the YouTube “recommended” list was this version of the very same song sung by a couple of celebrity singers:

It turns out that the Sesame Street version with Ernie and Bert is actually a version of an old folk song. Here is another version of it:

So the question is, how did Erica’s father come up with the Barth family’s George Washington Bridge song? Was it coincidence? Did he repress some memory of having heard the folk song? Could the rhythm of the sounds of words yield an almost identical musical phrase unconsciously?

I asked Peter Rosenthal, a partner at a New York City law firm specializing in Music Copyright law about the possibility of similar songs being written by multiple people in multiple places. He explained that in most cases of copyright infringement, the defendant will argue that it would have been impossible for him or her ever to have heard the alternate version of a song. Proving that they stole the song is difficult to do “unless you have videotape of the songwriter sitting with his guitar and a copy of the earlier record, transcribing the notes and adding his own lyrics,” he says. So cases instead rely on inference: The fact that songs are so strikingly similar means copying must have occurred.

However, the defense can be successful, such as in the 2002 case Calhoun v. Lillenas. Ronald Calhoun sued Lillenas Publishing over their song “Emmanuel,” whose chorus was notably similar to his hymn, “Before His Eyes,” which had been a church staple in Washington State in the 1970s. The court found that there was not enough evidence to support that the writers had access to “Before His Eyes,” and the case was lost.

Famously, George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” was accused of infringing on the Chiffons big hit, “He’s so Fine.” Harrison lost, setting the precedent for what is now known as “subconscious copying.” Harrison paid over a million and a half in earnings from the song but claimed the song was always “in escrow” and that he never made a cent from it. Even worse, perhaps, it inspired Harrison, in his frustration, to pen this song called appropriately, “This Song.”

A “George Harrison” is very likely what happened to Mr. Barth when he began singing his version of The George Washington Bridge Song. , Matt Thomas, PhD and Musicologist at Cal State Fullerton, agrees. “That melody is all over the place,” he says.

Further, the probability that the rhythm of words would yield the same tune musically doesn’t really occur very often. For example, Thomas points out the various applications of the word “Hallelujah” from Handel’s Messiah to the Leonard Cohen song and that they are vastly different.

Instead, Thomas suggests that an 1888 waltz called “Sobre las Olas” (Over the waves) by Juventino Rosas which was often played on carnival organs is a much more probable source, eking into Mr. Barth’s and the other George Washington Bridge songs’ “writers’” collective subconsciousness, or “subconscious copying.”

Peter Rosenthal points out that the Sesame Street version came out around the time the Barth daughters were young and suggests that might be the source of the song.

“It’s a normal process for writing a parody tune or children’s song,” says Thomas. “Our national anthem—O say can you see? That melody had different words originally. I believe it started as an English drinking song.”

For his part, Mr. Barth can’t remember for sure how his version came to be, but what he does remember are the memories. “We had fun singing that song,” he said. “We still do.”

Joselin Linder is an author based in Brooklyn. Her work includes The Gamification Revolution, Game-Based Marketing, as well as humor and relationship guides. She has contributed to NPR and is a Tedx presenter.