The North Carolina Supreme Court on Monday heard arguments about whether it should reinstate death sentences for four inmates whose punishments were reduced under a revoked state law that allowed criminal defendants to challenge their sentences by raising claims of racial bias. One of these was Marcus Robinson, a black man who was the first person to have his punishment reduced under the now revoked Racial Justice Act. One of Mr. Robinson’s lawyers, Donald Beskind, wrote the following blog post for Life of the Law. Listen to our executive producer Nancy Mullane interview him here.

A prosecutor in a North Carolina death penalty trial uses a peremptory challenge against a black juror. Why did he do it? When asked, he says it was because of the juror’s demeanor, body language or some other reason virtually impossible to disprove. How does he know to use that reason? His office has sent him to training on how to avoid giving an impermissible reason and he has received a “cheat sheet” with reasons to use.

The defendant’s lawyer objects saying that Batson v. United States makes the prosecutor’s purposeful discrimination a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection clause. The test the judge applies is whether purposeful discrimination was a significant factor in the prosecutor’s strike decision.

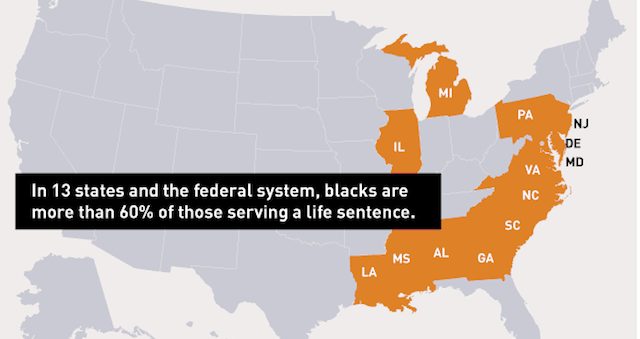

We know, of course, that intentional discrimination exists, but we know, too, that much discrimination is unconscious. What if a prosecutor is trying to be fair, but because of his upbringing unconsciously sees black people as inferior? To him a black person who has some drinking convictions is a “wino,” but a white person with the same criminal record is a “good ole boy.” In the moment when the judge has to rule on the Batson objection, can he or she understand the prosecutor’s purpose? The judge only knows the pattern of peremptory strikes of that prosecutor in that case and the reasons the prosecutor assigned for them. Not surprisingly, on that limited evidence, judges don’t like to call prosecutors racists, so across North Carolina, on average twice as many blacks than non-blacks are stricken in death penalty cases and the juries that hear death penalty cases are disproportionately non-black.

North Carolina, to its everlasting credit, sought to do something about death sentences in which race discrimination of any variety was a significant factor. It passed its Racial Justice Act in 2009. The Act said that any person with a death sentence who proved by the greater weight of the evidence that race (not intentional discrimination) was a significant factor in their sentence, would be re-sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole [LWOP].

One person, Marcus Robinson, had his case heard under the law and received relief. A more conservative legislature amended the law in 2012 to make proof more difficult, but three more people, two men and a woman, got relief. All four are now off death row and serving LWOP sentences. Finally, in 2013, the legislature entirely abolished the Act. Before that happened, most of those with death sentences in North Carolina filed for relief. Courts in the future will have to decide whether the abolition of the statute ended their right to seek that relief.

This Racial Justice Act was narrow in its scope—it applied to only death penalty cases. An inmate serving time for any other crime, even if race was a factor in his conviction or sentence, got no relief. The Act recognized that death at the hands of the state was different. It recognized the obligation of government not to take a life where race played any role in obtaining the right to do so—especially when the government’s own prosecutor’s chose to make the racially discriminatory strikes.

On April 14, 2014, the North Carolina Supreme Court heard the State’s appeal of the four Racial Justice Act cases decided thus far. The State argued that the judge who heard all four cases had it wrong and that proof of intentional discrimination was required under the Act. The State dismissed statistical evidence from a study by Michigan State University researchers that prosecutors in the County where all four were tried struck black jurors at 2.5 times the rate as non-blacks. It tried to justify the fact that in Marcus Robinson’s prosecutor struck 50% of the black jurors but only 14% of the white jurors, a 3.5 times as frequent strike rate—and that Quintel Augustine’s prosecutor eliminated every black juror—so Mr. Augustine was convicted and sentenced to death by an all white jury. In fact, counsel for these defendants argued to the justices, the statistical evidence alone shows systematic discrimination (whether intentional or unintentional) against black jurors. But beyond statistical evidence of discrimination in prosecution strikes across the state, the evidence the justices heard showed specific instances of discrimination against particular jurors in each of the cases.

Likely, it will be months before the Supreme Court renders its opinion. Until then four people wait to find out whether North Carolina’s little ray of racial justice will shine on them and spare their lives. Also waiting are the millions of black North Carolinians who hope that one day they will have an equal right to participate in the most important decision a juror ever makes. Their wait will be longer.

Don Beskind is a Professor of the Practice of Law at Duke University who argued Marcus Robinson’s case before the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Photo: Hatty Lee/Colorlines