Just over a year ago, I wrote my first article for The Life of the Law, “An Open Letter to the President,” about my and my partner Jodi’s struggle under America’s legalized discrimination against same-sex couples, specifically regarding immigration law.

I also sent this letter through good old-fashioned snail mail to the White House. I didn’t send it with tracking; I just sent it into the void placing my faith in the modern miracle that is the postal service, hoping that it would, somehow, reach President Obama.

I didn’t know, at the time, what letters undergo to reach the President. I knew from my religious watching of The West Wing that if you are a personal friend of the President you need to write a special code on your letter so that it makes it to him, wheat separated from the chaff of all the constituent letters. I knew from writing letters to presidents and other politicians during my childhood that they usually do reply eventually. I think I wrote to the first George Bush about war and to Bill Clinton about saving the rainforests. In my early twenties, The Honorable Representative Sue Myrick and I entered into a passive-aggressive correspondence in which I would write to her about various gay rights issues, including the “Permanent Partners Immigration Act” and its later incarnation as the “Uniting American Families Act,” bills specifically about immigration rights for same-sex bi-national couples. (I also wrote to Senator Patrick Leahy [D-VT] to thank him for sponsoring these bills.) In my letter to Sue Myrick, I wrote:

I know this is a sticky issue for you and you may think it doesn’t apply to your constituents, but I can promise you it does, and that it would help many of us begin to build the types of families we hope for. You do not have to support gay marriage to pass this bill, just the right of partners who wish for permanence to stay together. It provides the same immigration benefits for same-sex couples as for married couples—no special treatment, just the absence of discrimination.

Thank you for your time, and I hope you will reconsider your position on this matter.

Sue Myrick wrote back that she did not support any policies that allowed discrimination against any North Carolinians, but that she did not support same-sex marriage. I wrote to her reiterating that she did not have to support same-sex marriage in order to support those bills. She sent me the same reply as the first time.

From those experiences, I knew that the recipe for receiving a reply from a politician seems to be: Sift together equal parts passion and rhetoric. Let simmer, then roll out onto a sheet. Send letter. Let any remaining passion sit, refrigerated, for at least six months. Forget that you have ever written to the politician in the first place. Move on with your life and do not hope for a reply. When you least expect it, a reply will come. It will be a form letter, at best responding to the issue you actually wrote to them about. At worst, it will show that they did not pay attention to the content of your original letter.

So while my letter to President Obama was making its way across oceans, in and out of the bellies of planes and the bowels of trucks, being sorted and handled by Australian and American postal workers, and, I assumed, being dumped on the desk of whatever hapless intern tallies the topics of the President’s letters and issues the appropriate form letter in reply, I was doing my best to forget that I had ever sent it at all. I continued writing for The Life of the Law. I celebrated with Jodi on June 26th when DOMA was repealed, and wrote about that too. A dear friend from my childhood who is now an immigration lawyer offered to represent us pro bono in our petition for Jodi’s green card, and we got the application underway almost immediately. My sister came to visit us from the US. Jodi and I celebrated ten years of being together on August 14th. At one point I thought about my letter to Obama, still out there in the ether, and figured that now that my problem had been “solved” by the Judicial branch, it was probably a moot point to the Executive, and assumed that I might not get a reply since my issue was probably no longer as relevant as about, oh, forty million other things on the President’s plate.

Months went by. We held a Thanksgiving dinner for our Sydney friends, successfully fitting 18 people in our small apartment and bringing the joys of thankfulness and tryptophan to a group of uninitiated Australians. My mom came to visit from the US, and we spent Christmas in Western Australia with Jodi’s parents—the first time our families had ever met in our decade together. We watched the spectacular Sydney Harbour fireworks on New Year’s Eve, looked toward the future, and totally forgot the lonely letter mailed ten months prior.

On January 2nd, I went back to work (in the School of Education at the University of New South Wales), swamped with preparations for various events I had to run for the next month. On January 6th, my work pigeonhole, normally inhabited by invoices, memos, and paperwork to sign, was stuffed with a large manila envelope, marked “Do Not Bend” and plastered with Air Mail stickers, from The White House.

I honestly didn’t know what it could be. My first thought was that maybe it had something to do with Jodi’s green card application or my Australian permanent residence, even though neither of those explanations makes any sense. And then I realized that I had sent my letter to President Obama in a UNSW envelope—I had thought it would lend me credibility; show I was an upstanding member of society, and also showcase even more loudly that I was in Australia and not America. Inadvertently, that had meant that his reply somehow found me, among the 6,000 employees and 50,000 students at UNSW, by simply being addressed to:

Ms. Katherine Thompson

The University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

Australia

—no department, office number, or anything. As though I would be as easy to find as he is at the return address on his envelope:

The White House

Washington, DC 20502

I repeat: the functioning of the postal service is nothing short of miraculous, like flight, space travel, and cell phones.

I went back to my office. I stared at the envelope. The metered postmark read December 19, 2013 – the day that we had flown to Perth and my mother had met Jodi’s. I opened the envelope along its sticky flap. Inside was a piece of cardboard the size of the envelope and a small piece of cream-colored stationery embossed with the presidential seal:

December 12, 2013

Ms. Katherine Thompson

The University of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

Dear Katherine:

This is just a quick note to say thank you for the letter you sent earlier this year.

I applauded the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act. This ruling was a victory for couples like you who have fought for equal treatment under the law. The laws of our land are catching up to the fundamental truth that millions of Americans hold in our hearts: when all Americans are treated as equal, no matter where they come from or whom they love, we are all more free. But our work is not complete, and I want you to know that I will keep fighting for LGBT rights every single day I hold this office.

Thank you, again, for writing. I hope you and Jodi have a wonderful holiday season.

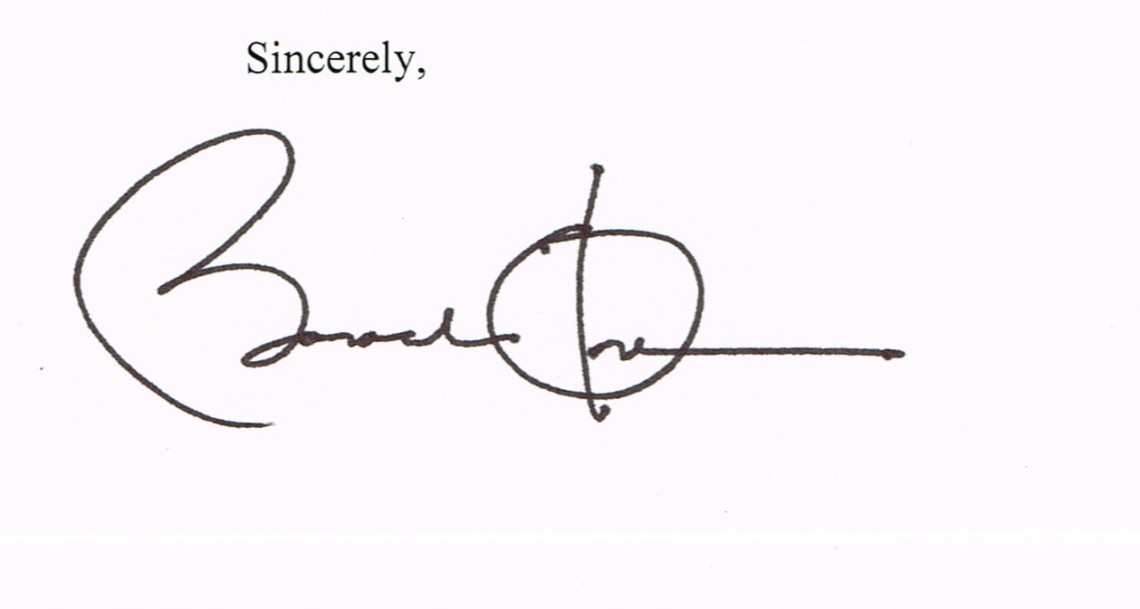

Sincerely,

Barack Obama

I felt like I had a potato in my throat. This was no form letter, and I could see the bleeding of the ink at the edges of his so-real signature. This was a letter with texture—embossing, watermark, handwriting, names. President Obama knows my name and Jodi’s! He thanked me twice! He wishes us happy holidays. My heart was racing and my face was plastered with a silly grin of the kind that for some reason seems reserved for children; adults censor such smiles in public. I kept the news to myself all day, a precious little gift that I returned to, savoring it again in the quiet moments.

When I got home, I shared it with Jodi and my mom (who was still visiting us from the US). I scanned the letter and shared it on Facebook. I tweeted it. The scan quality was not commensurate with the quality of the paper or the raw humanness of the signature, but even without the texture it got the point across. I felt so…special, so loved by my country, so different than I had a year earlier, when I had just arrived in Australia and was nursing the fresh wounds of leaving home.

A friend of mine on Facebook shared the article I referenced above, a New York Times feature from 2009: “Picking Letters, 10 A Day, That Reach Obama.” Through that and a great video on The White House blog, I learned what my letter had undergone. It was chosen out of thousands received on the same day (65,000 paper letters each week) to be one of hundreds that ended up on the desk of Mike Kelleher, the Director of White House Correspondence. And from those hundreds, Mr. Kelleher chooses ten each day to give to the President, trying to give him a snapshot of what real Americans’ problems and concerns are, and what their daily lives are like. The video shows Mr. Obama writing back (usually to 3-4 letters each night by hand—left-handed, like me). In 2009, my New Year’s resolution was to write a letter to someone every day, and I made it six weeks into the year before I had to abandon the project. So to write 3-4 letters a day, on top of being the President, and when you know you have 6-7 more from the same day piling up, strikes me as an amazing, if Sisyphean, endeavor.

His letter to me is not handwritten (other than the signature), but it’s definitely personal. It must have been read by at least one intern or staffer, Mike Kelleher, and the President. I like knowing that it was read by multiple people—not just those who encountered it through Life of the Law, but individuals who handled the letter itself and who would have had personal reactions in addition to evaluating it for its suitability to send on to the President. I have found myself wondering not just about the physical journey of my letter to him, but also how it fit into his consciousness over the months between my sending it, his receiving it, and his writing back. I’m guessing that he had read it well in advance of the overturn of DOMA on June 26th—I wonder if he thought of us that day; I wonder if he ever thought of us during his speeches or town hall meetings when the issues of LGBT rights or immigration arose. And I wonder what finally prompted him to write—simply getting through the epistolary backlog, or wanting to wait until he had something positive to share, or something about the holiday season. While I realize that it isn’t directly a result of Obama’s own actions that our situation is now so radically improved, I still think the climate he has created in the government (not to mention the appointment of Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan to the Supreme Court) has been more conducive to the advancement of LGBT equality than any administration in history. I like to think that he was saving my letter until he could give me a response I deserved, which would be something that would give me hope. When DOMA was overturned, maybe he still wanted to wait until he saw how the results played out in the various arms of government, lest that hope turn out to have been false. And maybe when the holidays were upon him, and he had a moment, in the Christmas-treed quiet, to reflect on the year behind him, one of the things that stood out to him was the moment, on June 26th, when we all became more free, and the letter he had from someone half a world away that brought that feeling to life for him.