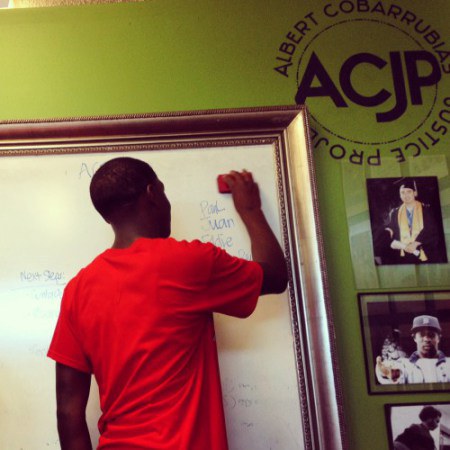

Tony is 13 years old and just got out from 99 days in juvenile hall. He sits shyly at the edge of the table next to his mother and responds respectfully to the “congratulations” and “welcome homes” that are directed to him from strangers who know him only indirectly, through his mother’s stories and from seeing his name on a whiteboard at the meeting they all attend every week. Tony is at what we’ve dubbed our “family justice hub” meeting — a weekly gathering of families whose loved ones are facing criminal charges. He is here to be a part of the one ceremony we have: When a family brings a loved one home either by beating the charges, or by receiving a reduced sentence or a dismissal — they get to erase their name from the board. The room of roughly 20 people breaks into applause when Tony takes the eraser to his name. His mother thanks the people in the room who walked with her and her son through the darkest 99 days of their lives. Tony was facing years of incarceration, but due to her advocacy and the public defender’s lawyering, her son will be able to spend his fourteenth birthday at home.

If tradition holds, Tony’s mom will continue to come to the meetings, assisting other families who find themselves in the position she did. She will share with them what she learned here from others — how to partner with or push the public defender, how to dissect police reports and court transcripts, and how to build a sustained community presence in the courtroom to let judges and prosecutors know the person facing charges is not alone.

We call the approach “participatory defense,” a community organizing model for people facing charges, their families, and their communities.

As incarceration rates balloon to astronomical levels – 1 out of 100 Americans are currently locked up — participatory defense may be the most assessable way directly affected communities can both challenge mass incarceration and see timely and locally relevant results of their efforts. It is a penetration into the one domain that facilitates people going to prisons and jails, yet has been left largely unexplored by the ground up movement to end mass incarceration: the courts.

We have been developing the participatory defense model in San Jose, California for six years. The meetings are now facilitated by people who first came for their own cases, volunteers who have transformed from isolated mothers forced to sit idly as their sons were chewed up by the courts to vocal advocates who help navigate and encourage other families.

Participatory defense meetings are not legal clinics. There are no lawyers in the room, but in many respects, that is the point. From a movement-building sensibility, the case outcome is not the only measuring stick, but also important is whether the process transformed someone’s sense of power and agency. It is why we don’t use the word “client” in our practice. Because to be a client presumes that the person is the recipient of a service or change, rather than the key actor responsible for that change.

The tangible impact of family and community participation on cases is undeniable. We have seen acquittals, charges dismissed and reduced, prison terms changed to rehabilitation programs, even life sentences taken off the table. When we tally the total number of “time saved” (as opposed to “time served”— from all of our cases collectively over six years — by looking at the original maximum sentencing exposure someone was facing versus what the individual received after family and community intervention — we see over 1,600 years of time saved.

Eight out of ten of the roughly 2.5 million incarcerated were been represented by a public defender. That means, in short, improving public defense is arguably the least talked about, yet statistically significant way, to challenge mass incarceration as we know it. For this reason, finding ways for the family and community to partner with the public defender assigned the case could be a real game-changer nationally.

This is already happening to some extent. A group called the Community Oriented Defenders Network, which includes over 100 public defender offices, just met to share new approaches that challenge the status quo of indigent defense. In New York, the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem and the Bronx Defenders are practicing holistic defense, attacking the contextual issues of poverty that force clients into the criminal justice system. In the South, Gideon’s Promise is giving elite training to defenders to face some of the toughest courts in the country. In California, the Alameda County Public Defender is now representing their clients in immigration court, and the San Francisco office has launched a system-wide study of how racial discrimination plays out in the courts – both are unprecedented approaches in state history.

But as forward thinking these advancements of public defender offices are, they are still inherently limited to what lawyers can do. What about the what the communities they represent can do that they aren’t doing, yet?

Make no mistake. Right now, across the country, there are parents sitting steadfast in courtroom pews in solidarity with their children facing a hearing, and church pastors writing letters to judges for an impending sentence. Such initiative evidences the ubiquitous possibility of participatory defense. If these actions though were thought of as activities part and parcel of a larger, named practice rather than isolated responses, a more profound, sustained reshaping of the criminal justice system could occur.

Participatory defense is not a static invention or program, but a naming of an inclination that already exists in communities across the country in order to advance its potency and impact. There is a forward-moving power in naming an impulse.

In a slight pivot of perspective of who can be the system-changers and how — the millions who face prison or jail and their communities, those waiting in line at court everyday — those very people could transition from fodder of the criminal justice system to the agents who bring the era of mass incarceration to its rightful end.

Raj Jayadev is giving trainings to organizations and public defender offices interested in participatory defense. To learn more, reach him at raj@siliconvalleydebug.org or visit acjusticeproject.org.