The Bill Cosby sexual predator story line just keeps spooling along, and now it has led to a discussion of whether the Associated Press and its entertainment reporter, Brett Zongker, violated some standard of journalistic “integrity” when the AP released parts of a Cosby interview that had not been released earlier.

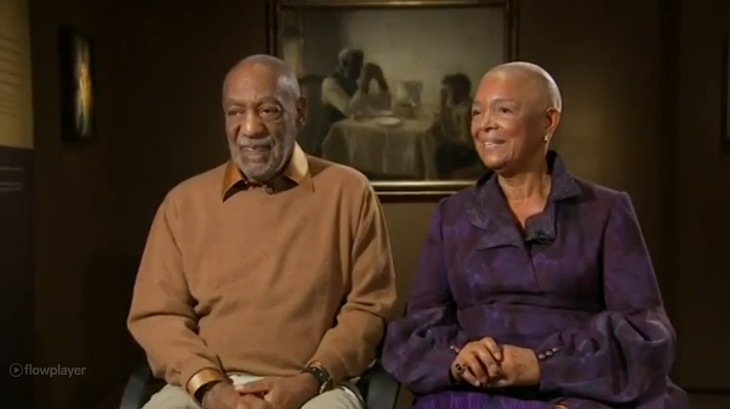

“Integrity” is what the entertainer admonished his interviewer and the AP to display as he was wrapping up an interview that was supposed to be about Cosby and his wife, Camille, loaning a collection of African-American art to the Smithsonian.

At one point, Zongker tried to ask Cosby about, well, you know, and Cosby wouldn’t respond. As he and his wife were leaving, Cosby asked Zongker to “scuttle” the part of the video of him refusing to comment. Zongker said he would ask his bosses, “and I’m sure they’ll understand,” but he never made any promises.

AP at first didn’t release that part of its video. But as the Cosby story continued to gather momentum, it did make the entire video available, including the part in dispute. In the video, Zongker pointed out to CNN’s Brian Stelter, “no one actually said the interview was over, or that a particular part was off the record. Nobody said, ‘let’s turn off the camera.’ The cameras kept rolling.

Like many questions in journalism ethics, there are nuances and complications. But to the basic question — was this a breach of a long-honored journalistic convention? — my opinion is that the answer is clearly “no.”

There are a few laws that apply to the release or non-release of information. Journalists have gone before grand juries and even to jail because they refused to reveal a source. And they’ve faced civil suits when they’ve broken a promise of confidentiality.

But for the most part, the questions about protecting a source or promising not to report something are ethical questions, not legal ones.

The law is about what you can do as a journalist; ethics is about what you should do.

When the Society of Professional Journalists decided it was time to update its widely used ethics code, one of the concepts the drafting committee wanted to emphasize was transparency. In fact, we wanted to get the actual word in there. There were a number of principles in the earlier version of the code, adopted in 1996, that clearly alluded to a preference for doing things openly and straightforwardly, but the word itself was missing.

As the recently revised SPJ Code of Ethics points out, “The public is entitled to as much information as possible to judge the reliability and motivations of sources.”

Here’s how the AP Stylebook defines the various levels of secrecy:

On the record. The information can be used with no caveats, quoting the source by name.

Off the record. The information cannot be used for publication.

Background. The information can be published but only under conditions negotiated with the source. Generally, the sources do not want their names published but will agree to a description of their position. AP reporters should object vigorously when a source wants to brief a group of reporters on background and try to persuade the source to put the briefing on the record. These background briefings have become routine in many venues, especially with government officials.

Deep background. The information can be used but without attribution. The source does not want to be identified in any way, even on condition of anonymity.

It’s all right to use “off the record” information as the basis to pursue an “on the record” story, with identified sources.

It’s an agreement between reporter and source, and it doesn’t work if the two of them aren’t operating from the same premise.

It should come at the beginning of an interview or news conference, or whatever the newsworthy encounter, not at the end. “Oh, by the way, that was all off the record,” doesn’t work after the words have been said or the images recorded.

Here’s another quote from the SPJ Code: “Realize that private people have a greater right to control information about themselves than public figures and others who seek power, influence or attention.”

Bill Cosby is a public figure, and he’s been around long enough to know that you can’t put toothpaste back into the tube without getting very messy.

Fred Brown was a columnist at The Denver Post for most of his career and now teaches media ethics at the University of Denver. He is a former national president of the Society of Professional Journalists and served on the drafting committees for the 1996 and 2014 SPJ ethics codes.