The students in my sophomore classes are currently studying medieval literature. This week while discussing Beowulf, I pointed to the part of the epic when Beowulf is dying and sends Wiglaf, his loyal follower, to bring forth treasure from the dragon’s lair. Initially in the text, the request to view the treasure seems oddly greedy, and I asked my students if they were on their deathbeds and could set eyes on anything, would they want to see their gold? Or, would they want to see their loved ones? A lively discussion ensued in which I mentioned that I would definitely want to see my husband and children. A young man in my class replied in the most casual way, “Well, you wouldn’t have gold to look at because you’re a teacher.” This student is not typically rude or inappropriate. He wasn’t trying to make a joke at my expense. The fifteen-year-old had, however, absorbed our nation’s great devaluation of the teaching profession.

Sources examining reasons for teacher turnover are plentiful. In her article, “Why Do Teachers Quit?” Liz Riggs examines why turnover in education is 4% higher than other professions. Her interviewee Richard Ingersoll, professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Education and former high school social studies and algebra teacher, says, “One of the biggest reasons I quit was sort of intangible … But it’s very real: It’s just a lack of respect. Teachers in schools do not call the shots. They have very little say. They’re told what to do. It’s a very disempowered line of work.”

Ironically, we teachers are given tremendous power in the lives of our students. Like the bumper sticker says: Teachers make all other professions possible.

The other reason highlighted in Riggs’ article is poor compensation for emotionally charged labor. My average work week is no less than 55-60 hours. My colleagues and I spent our summer vacations lesson-planning and attending professional development sessions. I am guilty of neglecting the needs of my own children at times in order to serve the needs of my students. And that is why this particular week, that comment from a sophomore student not only hurt but also demanded me to consider my profession and its shortcomings.

I can’t ignore the connections between respect and compensation in spite of my idealism and passion for teaching. I’m simply not sure where to begin when it comes to reinstating the value and respect my profession deserves. My colleagues discuss solutions. One of three male teachers in our department (of twelve, total) insists that if more men were in the profession, salaries and respect would be significantly higher. A female teacher interjects that male teachers still earn more than their female counterparts in most districts. Talk about a hornet’s nest. A second-year teacher, who is female and attractive, argues that the teaching profession has been sexualized in the media such that titillating stories of scandalous and criminal student-teacher sexual encounters contribute to a great mistrust of teacher ability and intent—again, the discussion becomes a hornet’s nest.

Why do teachers make so little? It is, of course, a matter of budget and policy, and often, I wonder if it has something to do with the fact that so few policymakers have been educators. Those of us who have earned our certificates and put in the hours understand the inner workings of diverse classroom settings and demanding professional expectations in a way that others do not — beginning with the challenge we ourselves face as under-compensated shapers of the future. According to the Congressional Research Service’s Membership of the 113th Congress: A Profile, the most common professions practiced prior to congressional appointments are in the fields of business and law. The National Association of Colleges and Employers places starting salaries for those in business management or administration at $57,229, and a lawyer’s average starting salary at $75,804. An educator’s average starting salary is $40,267. (The second-year teacher scoffed when I repeated the educator’s starting salary—think lower. Much lower.)

Business and law salaries often have built-in yearly bonuses. In my state, Arizona, “performance pay” passed in 2000 under Proposition 301 was originally intended to provide public educators with a yearly scaled bonus. However, many states have turned such funding into a series of hoop jumping. For example, in order to qualify for my 301 pay which averages around $1500, I have to attend and work at three after school events, help meet my school’s overall academic goals, and serve as a sponsor, or on a variety committees, as well as increase my professional development hours (in addition to my certification renewal requirements). Gee, thanks! Remember how I was already working 60 hours/week? Add to that being a mother of two kids, a writer, and a wife.

Our new federally mandated, now highly politicized and often state-by-state rejected evaluation systems were originally intended to be sure teachers are achieving standard-based learning gains with their students. This has required hours of new data tracking, implementation and professional learning committees to address and interpret the data. However, salaries at most schools across the nation haven’t budged, and in some cases, overall funding of public education has decreased. What would happen if teachers were compensated in parallel with the mid-career salary rates afforded to other licensed professions?

The Equity Project Charter School (TEP) in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York decided to find out. According to TEP’s philosophy, “TEP teachers are valued and sustained through revolutionary compensations; a $125K annual salary and the opportunity to earn a significant annual bonus based on school-wide performance.” How do they afford to pay their teachers so well? “TEP has created a sustainable and conservative financial model that allows the school to compensate its teachers appropriately without relying on outside private funding … In short, hiring and paying master teachers what they are worth is a cost-effective mechanism for boosting student achievement.”

And it’s working. Analyzing long-term results, researchers report, “Students who attended TEP for four years had test score gains equal to an additional 1.6 years of school in math, slightly less than half a year in English, and slightly more than half a year in science.”

There appears to be a direct correlation between the motivation to perform well as an educator and being compensated well.

Because teaching is so emotionally taxing—the best teachers become invested in their students’ successes — I wonder if teachers have rolled over a bit, if we have essentially gotten used to being kicked around because what’s most at stake for those of us who are passionate is our students, their individual and academic growth. But just because I look forward to teaching every day, and love what I do so entirely that at times it doesn’t feel like a job, doesn’t mean that it isn’t one — a critically important one. How can our students respect their learning environments if the nation at large doesn’t adequately respect those in charge of such environments? As demonstrated in my classroom this week, the unfortunate and irrationally low valuation of teachers has made its mark.

Jessica Burnquist lives in Arizona, where she is a writer and teacher.

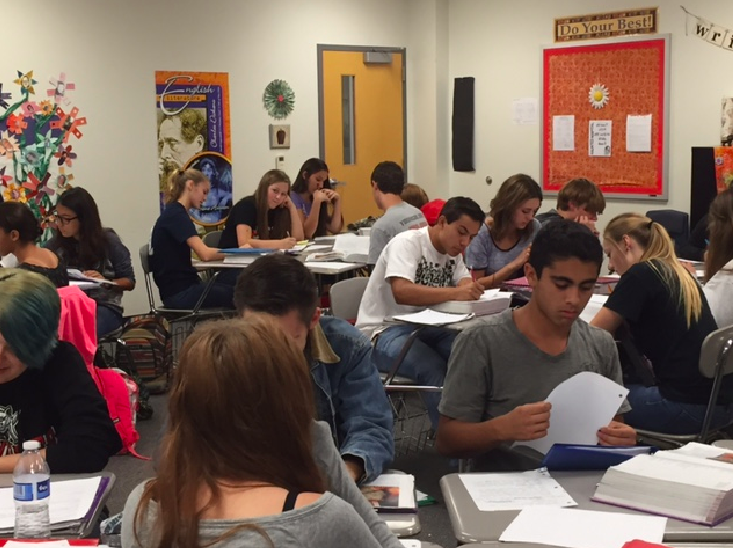

Image: The author’s classroom / Jessica Burnquist