9/22 Episode: WHO’S THE CRIMINAL?

This week, we ask a simple question: Who counts as a criminal?

Is a criminal anyone who’s ever committed a crime? Or just someone who’s been arrested? Or convicted? Or gone to jail?

What about people who’ve been sent to prison and gotten out. They did the crime, served the time… are they still criminals?

Somewhere between a quarter and a third of all Americans have criminal records. So how you answer it –– and how employers, colleges, and social service agencies answer it –– has huge effects on many people’s lives. And those effects, as you might imagine, vary widely according to race, class and geography.

So, who is a criminal? We sent Nicole Pasulka to find an answer. Listen to Life of the Law’s latest feature episode, here.

Radio Stations: You can find our new episode here on PRX, Public Radio Exchange.

![]()

Reporter’s Notebook: Nicole Pasulka

While Graham was on probation for a drug charge he even had a letter stating that his arrest wasn’t a conviction and shouldn’t be held against him by prospective employers. That letter didn’t stop a number of organizations from rejecting him on the grounds that he’d been arrested for a drug crime.

Cumberbatch had come to the United States from Guyana when he was four. In 2014, after he’d served his sentence and completed his probation for the robbery conviction, he was placed in immigration detention for five months. He would have been deported if not for a huge community effort to get him released. He’s since been pardoned by New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo, one of only five pardon’s granted by Cuomo.

What the Law Looks Like: The Refugee Crisis

As the refugee crisis bewilder the nation states of the Middle East and Europe, the Obama Administration said this week that the United States will more than double the number of worldwide refugees it accepts each year, from 70,000 to 170,000. As talk about immigration law builds to the 2016 presidential election, this photo serves as a reminder of what’s at stake around the world: lives.

![]()

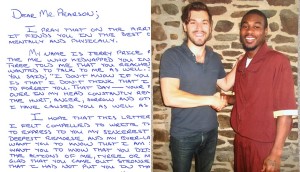

LOTL Staff Review: What Happened After My Kidnapping

It’s a weird thing to say but Bradford Pearson was probably a good person to kidnap. For one thing he had no interest in fighting back, so the situation didn’t escalate to serious physical endangerment. But more importantly, Bradford is a journalist, which means he turned his own frightening experience into a brilliant piece of storytelling.

After being abducted and robbed in Philadelphia as a teenager in college, Bradford’s life was changed forever. He would think about the episode frequently. At first, his memories of the kidnapping prevented him from leading a normal life. Eventually, though, he recovered and discovered normalcy.

The same can’t be said for the three men who kidnapped him. Incarcerated for decades the lives of these men were ruined by the crimes they chose to commit. Bradford discovered this after finding his captors; meeting two of them in prison; and comparing his life to their very different lives.

In this first-person narrative for Philadelphia Magazine, Bradford explores the limits of forgiveness and rehabilitation within a criminal justice system that so often discourages both.