It’s been over 60 years, but Henrietta Massey still remembers Jim Thorpe’s funeral. His first funeral.

“Gosh, it was kind of like a shocking day for me,” said Sandra Massey, a tribal elder with the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma – Jim’s tribe. “I was about maybe 16 or 17 years old, and we had gone to the funeral held at the Ed Mack farm. It was a Sac and Fox ceremonial – a traditional ceremonial.”

Henrietta remembers going to a special building made of scaffolding with a big fireplace in the middle. Jim’s coffin was there, too. There was a feast meal and an elderly member of the tribe began addressing the Tribe’s spirits. But then, right in the middle of everything, a hearse backed up to the house and out stepped a couple guys in suits.

“As I recall, these gentlemen came in and said that [Jim’s] wife wanted the body taken,” said Henrietta. “So they took it. They got the body and took it out of that house and put it in the hearse and took off.”

But it gets stranger. Jim’s wife, Patricia, had signed a contract with a pair of towns in Pennsylvania – towns that Jim had never even been to — saying that if they consolidated under the name “Jim Thorpe,” and if they built a really nice memorial, they could have her husband’s body.

Can a wife really show up at a man’s funeral, take his body away from his friends and family, and do whatever she wants with it? And is there anything the family can do about it? Usually this is a simple question of state probate law. But Jim was Native American — so the answer is not so simple.

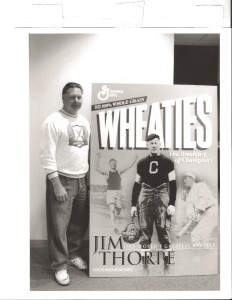

Jim Thorpe was the undisputed superstar of the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. His performances in the decathlon and pentathlon earned him two gold medals and he was welcomed back to the US with a ticker-tape parade down Broadway. People said he was the greatest athlete in the world–and that was before he went on to play pro football and pro baseball.

But when Jim got too old to play sports, things changed. He moved to California and took bit parts in cowboys-and-Indians flicks. He drifted. He drank. He went broke.

Jim married his third wife, a former lounge singer named Patricia, on a trip to Tijuana. He was 57. Patricia wanted to make the most of her new husband’s fame. So there were some autograph signings and some public appearances. A bio-pic starring a bronzed and buffed Burt Lancaster. But nothing paid that much. So Jim kept drifting.

“And I have never in my life, and never have since then seen anyone come in and be as disrespectful as that was”

—Henrietta Massey

Jim died of coronary sclerosis in 1953. He was only 65. And at first, Patricia didn’t even claim Jim’s body. Jim’s family had it sent to Oklahoma — where Jim had grown up — for a traditional Sac and Fox funeral. Jim’s sons said that it was what Jim had wanted. But then those guys with the hearse showed up and they left with Jim’s body.

“And I have never in my life, and never have since then seen anyone come in and be as disrespectful as that was,” said Massey. “These rites were given to us by God. And we were following them and then to see this?”

Nobody challenged Patricia at the time. State law defines who can make the initial decision of what do with a person’s body and it’s usually the spouse. If someone else wants that right they can try to get a court order. But in Jim’s case nobody tried.

Patricia wanted Jim to have a monument but Oklahoma wouldn’t pay for one. So Patricia started to look around for someone who would. She was in Pennsylvania meeting with the head of the NFL when she heard about two fading coal towns called Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk.

***

To get to the (two) Mauch Chunks, you follow the twists of the Lehigh River through eastern Pennsylvania to a steep-walled gorge covered with sandstone outcroppings and hickory trees. The coal inside these mountains built fortunes and coal kings and railroad barons built ornate mansions that still line the streets downtown. But by the 1950s the coal boom was over. The town was desperate for something, or someone, to turn things around.

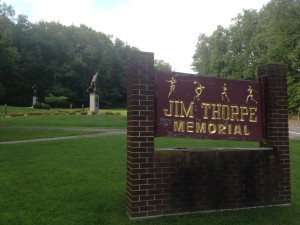

I heard the story of how the Mauch Chunks became Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, from a guy named Jack Kmetz. He’s the president of the Jim Thorpe Area Sports Hall of Fame; a former high school basketball star in nylon shorts and tube socks . We met at Jim’s mausoleum which is off a two-lane highway heading north out of town.

. We met at Jim’s mausoleum which is off a two-lane highway heading north out of town.

Jack says you have to start by understanding just how bad things were here in the 1950s. Once the coal was gone, the railroads were gone, too. Unemployment was out of control. Then somebody came up with a plan known as the “nickel a week club.”

“Every Saturday, every man, woman, and child would throw a nickel into their boxes, canisters, whatever they had,” said Jack. “And at the end of five years, they’d have $75,000 to draw some kind of employer here.”

Jack says that Jim Thorpe’s wife Patricia heard about the campaign–and she showed up in the one day with a little dog she had, and a proposition: how would the towns like to become the final resting place of her famous husband?

There were a few conditions, though: they had to build a suitable monument within three years and they had to change their name to “Jim Thorpe.”

The towns said yes.

Today, Jim still lies in the middle of a circular driveway surrounded by trees. There are two bronze statues — Jim dashing with a football; Jim hurling the discus — and an abstract sculpture meant to evoke Jim’s Native name, which translates as “Bright Path.” In the middle sits the mausoleum. It’s about the size of a refrigerator, and its carved with images of Jim.

“That’s the shot put. This is the discus. This is the hurdles, here,” said Jack Kmetz, walking around the mausoleum. “Around the side, he’s playing baseball. That’s the high jump.”

This is where Jim was finally laid to rest in 1957 — four years after his first, interrupted funeral. Jack was only a kid at the time, but he remembers how excited everyone was. He paraded with his little league team up Route 903. His brother was born that month and his parents named the baby Jim Thorpe Kmetz.

“It was a big day,” said Jack. “There were a lot of expectations. Most of them failed. And that’s part of why old-timers in the community are pretty much down on the fact that nothing ever materialized. But . . . we were very close to becoming a national shrine.”

People tell different stories about what Jim’s body was supposed to do for the town. Some say it was supposed to bring tourism. Or a football hall of fame. Or that there would be a memorial foundation that would build a hospital. But whatever it was that the towns were promised, or dreamed of, never happened.

“My personal opinion? Send him back and change the name back to Mauch Chunk.”

—Michael Nonnemacher

Decades later, the town did develop a thriving tourism industry. But it’s built around whitewater rafting and the scenery, not Jim. And to this day, the people of Jim Thorpe remain divided over their namesake.

“His widow was a big windbag. It was a big scam,” said Michael Nonnemacher, a tour guide in a local history museum. “Supposedly she got $10,000. I don’t know if that’s true. My personal opinion? Send him back and change the name back to Mauch Chunk.”

But no matter how locals feel about it, Jim Thorpe is lying exactly where his wife laid him to rest. And under the law, that’s usually where things end.

“Our people are sitting in boxes and shelves, even now, still today, being treated as collections, but these are people!”

—Sandra Massey

But Jim Thorpe was Native American. And Native American remains are — at least sometimes — covered by a federal law called NAGPRA: the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Congress passed the law in 1990 because it decided that Native American bodies were being treated like property. Their graves were looted. Their skulls were collected from battlefields. Their bodies were stuck in museums.

“Our people are sitting in boxes and shelves, even now, still today, being treated as collections,” said Sandra Massey. She’s the daughter of Henrietta, who was at Jim’s first funeral and is the Historic Preservation Officer of the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma. “But these are people!”

NAGPRA requires museums that have Native remains go through a proceeding to decide whether those remains should be returned to the families or tribes of the deceased. But the law defines “museum” as any institution that receives federal funds and has Native American cultural objects, which includes remains. And that means the town of Jim Thorpe could be considered a museum. So in 2010, one of Jim Thorpe’s sons used NAGPRA to file suit against the town of Jim Thorpe, seeking the return of his father’s body to Oklahoma. When that son died in 2011, the Sac and Fox Nation, along with two of Jim’s other sons picked up the suit.

This is clearly not a normal NAGPRA case. The people of Mauch Chunk didn’t want Jim as some kind of a Native curiosity. They wanted him as an athlete. And Jim’s not sitting in a box on a shelf somewhere. He was buried by his wife. But she did kind of treat him like property. And the point of NAGPRA is to make sure that deceased Native Americans are treated like people.

“The way the law is written, it’s not meant for this particular situation”

—John Thorpe

“Jim Thorpe is being treated like a relic right now,” said Sandra Massey. “He’s not being treated as a human being. And that’s what NAGPRA brings into law.”

But maybe it doesn’t.

“The way the law is written, it’s not meant for this particular situation,” said John Thorpe, Jim’s grandson. He opposes the lawsuit.

“My good buddy Ernie LaPointe, Sitting Bull’s great-grandson, dealt with NAGPRA because the Smithsonian had some of Sitting Bull’s leggings and a lock of his hair,” said John. “Those are the type of things that NAGPRA was designed to help Native Americans with.”

John says that if his grandfather is lying in a “museum” under NAGPRA, then there are a lot of modern-day Native Americans lying in museums — and that Congress didn’t pass NAGPRA to solve family disputes over their graves. That’s what John says is going on here: a family dispute. He says that even if Jim’s sons wanted their father in Oklahoma, Jim also had daughters who wanted him to stay in Pennsylvania. Especially Jim’s daughter, Grace–John’s aunt. She died two years before the suit was filed, and John says that’s no coincidence.

“She did it and it’s done and over with and he’s in the ground. Now leave him alone.”

—John Thorpe

“If by chance, my grandpa had told my Aunt Grace that he wanted to be buried in Oklahoma, my grandfather would be in Oklahoma,” said John. “You didn’t mess with Grace, and all the boys knew it. All my uncles knew it. And that’s why they waited for her to go away. They didn’t want to mess with Aunt Grace, man, nobody wants to mess with Aunt Grace!”

To John, it’s “unNative” — that’s his term — to dig up and move a body. And that’s regardless what Patricia did to Jim’s funeral.

“Shame on her,” said John. “Terrible thing to do. But she did it and it’s done and over with and he’s in the ground. Now leave him alone.”

Leave him alone. Jim is at rest. That’s an idea that’s popular in Pennsylvania, too.

“I gotta believe,” said Jack Kmetz, “that Jim Thorpe, if he’s floating around here maybe about 15,000 feet above us, he has to have a smile on his face looking at this here. It’s a pretty nice gravesite. And I don’t think Oklahoma can do anything like we have.”

The town also has a birthday celebration for Jim every year. They hire a Native American to lead the ceremonies — but he’s Apache, not Sac and Fox, like Jim was. So some people — non-Natives — say they’ve seen signs that Jim is at rest: smoke that defied the laws of physics, or a red-tailed hawk circling overhead. But Sandra Massey, the Sac and Fox Historic Preservation Officer, says stories like that are just one more reason why Jim should be moved back to Oklahoma to be with his own people.

“Yeah, he wants to be here because of some butterfly flying across our face or something like that,” she said. “To say this kind of stuff says they know nothing about who we are, nor do they care. Don’t care about Jim Thorpe to say that kind of stuff.”

But Jim is not going anywhere. When his case reached the Third Circuit, the judge held that NAGPRA doesn’t apply to his remains. The judge used a doctrine called absurd results. That means that read literally, Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, may seem like a museum. But – the judge held — Congress could not possibly have meant for federal judges to be mediating family disputes.

The Tribe appealed to the Supreme Court. They argued that NAGPRA’s repatriation proceedings can handle family disputes. But the Court didn’t take the case. That means that for better or worse, Jim’s body is going to stay in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania.

I certainly don’t know where Jim Thorpe should be buried.

But it’s kind of amazing that even now, when the Internet allows us to be everywhere and to last forever, where we are physically buried still matters.

For decades, Jim Thorpe was a household name. He’s been the subject of books and films. He’s all over the Internet. But the Internet is really big, and at some point, to find his achievements you have to know to look for them.

In eastern Pennsylvania, though, Jim’s name has been chiseled in granite. His face has been immortalized in bronze. He is literally ON the map. For generations to come, people are going to be asking, “so who was Jim Thorpe?”

But then again, maybe Jim wouldn’t have wanted to be remembered by strangers stopping at a roadside attraction. Maybe he’d just want to be remembered back home.

“Here, he was Jim,” said Sandra Massey. “He knew a lot of people. If you talk to people here, they remember how he hunted. How fast he could run. How high he could climb. I grew up hearing people call him ‘Dad,’ and it wasn’t “My dad the famous athlete,” it was ‘Dad.’ He was a person here. And that’s how people remember him. And that’s how he should be remembered.

When I asked John Thorpe how he thought his grandfather would want to be remembered, he had three words:

“Not like this!” he said.

PART II: The law and NAGPRA? A conversation with Scholar Sarah Harding

The law around Native American rights and disputes is complicated, and fascinating. Sarah Harding is an Associate Professor of Law and Chicago-Kent College and she’s an expert on NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

Sarah Harding: There’s certainly case law out there that has specifically addressed the question of whether people own their own bodies. But, the courts tend to sort of shy away from recognizing that your body is property. I think the reason why NAGPRA separates out Native American remains is because traditionally Native American remains didn’t have any of the protections that non-Native Americans actually were entitled to. So family members have the rights to control what happens to the remains of their loved ones or have the right to protect a gravesite, for example. Those protections traditionally did not apply to Native Americans On the one hand they were collected for scientific reasons. On the other hand, or in addition they were also collected just as curiosities. You know there’s heaps and heaps and heaps and heaps and heaps of skeletal remains in museums, not just across the U.S. but across the world. Certainly the Smithsonian itself had hundreds of thousands of human remains as well. So it was just open season on human remains. At least with respect to Native American human remains. So again NAGPRA is very much about trying to reverse that history of abuse and disrespect.

This is an interesting and complicated case without a doubt. But, I’m not sure it’s so clearly falls outside of what NAGPRA was intended for. I mean to begin with, without a doubt the town of Jim Thorpe is in fact or does in fact clearly fall underneath the definition in the legislation. Even the Third Circuit noted that. So that’s why they ended up sort of moving from, “Ok. Clearly it applies to this town. But this would just be absurd so we’re going to veer away from the clear textual wording of the legislation and do something completely different.”

The second thing is that simply because this is a dispute between, well essentially a dispute between family members it doesn’t mean it doesn’t still sort of smack in some ways of the various elements that NAGPRA was designed to address. If there was a clear indication that Jim Thorpe wanted his remains to be in this small town in Pennsylvania or even there was a clear indication that he did not want to be buried in a Native American traditional way in Oklahoma, then you know obviously we probably wouldn’t be having this discussion. Right? So I’m not saying that I think the decision was wrong and that the remains should be moved back to Oklahoma, I’m just not so certain as the court was that this clearly falls outside of what NAGPRA was designed to remedy.

There’s a very specific definition in the legislation that recognizes again that a museum or any institution that receives federal funding that might have some human remains in their possession may have a right to keep those human remains if it’s clear that they have them with the consent of the next of kin. That appears in the definitional section of NAGPRA. It’s not so clear how that gets operationalized in the repatriation provisions. But, that gives us an example that there is something in here whereby NAGPRA, you know, NAGPRA wasn’t intended to be completely left out simply because we’re talking about a family dispute.

Sarah Harding is an Associate Professor of Law at Chicago-Kent College of Law.

![]() PRODUCTION NOTES

PRODUCTION NOTES

Thorpe’s Body was reported by Rachel Proctor May and edited by Annie Murphy with sound design and production by Shani Aviram. Kirsten Jusewicz-Haidle and Jonathan Hirsch produced our segment with Sarah Harding.

Special thanks to Naomi Mezey of Georgetown University Law School, a member of Life of the Law’s panel of Advising Scholars for her production assistance.

Suggested Reading:

- Thorpe v. Borough of Jim Thorpe, 770 F.3d 255 (3d Cir. 2014), and Thorpe v. Borough of Thorpe, 2013 WL 1703572 (M.D. Penn., April 19, 2013).

- The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: Background and Legislative History, 24 Ariz. St. L.J. 35 (1992).

![]() This episode of Life of the Law was funded in part by our listeners and by grants from the Open Society Foundation, the Law and Society Association, the Proteus Fund and the National Science Foundation.

This episode of Life of the Law was funded in part by our listeners and by grants from the Open Society Foundation, the Law and Society Association, the Proteus Fund and the National Science Foundation.

© Copyright 2015 Life of the Law. All rights reserved.