Every week, a little bit of the law squeezes itself into local newspapers. Somewhere near the marriage announcements and death notices is usually a long list of dates, places, and alleged crimes. I am talking, of course, about police blotters.

At one point, police blotters served a useful purpose to a community. Neighbors could learn about and discuss the crime in their neck of the woods. Perhaps the week after a particularly egregious crime, vigilance would rise; residents would be more aware, keeping a closer eye on things, seeing something and saying something.

But today, police blotters are remnants of an age when news was less immediate, when Twitter wasn’t available as a crime-reporting tool, and when people still read print newspapers. The interesting this is, though, police blotters are still around, and perhaps even more interestingly, despite waning interest in printed journalism, people still care about local police blotters.

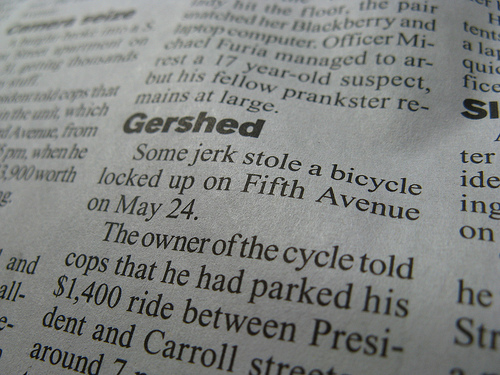

I care about police blotters because they make me laugh. Police blotters illustrate a fairly comical picture of the law, and yet, they still have a certain gravity to them that makes them unlike any other source on the nature of the living, breathing law.

The second most expensive zip code in the United States is Atherton, California. As you might expect, crime in the city is minimal. Think: vandalism of city signs and stolen potted plants from front porches. Reading the police blotter for the city gives you a pretty distinct portrait of what concerns citizens, day to day, in their community. A few years ago, a reporter at a local newspaper, the San Jose Mercury News, collected some of the best (read: funniest) entries from the city over the years. Here are a few favorites:

A man was reported to be sitting down and talking to himself. Police made contact and confirmed he was using a cellphone.

A resident worried that a noisy hawk in a tree was in distress. When authorities arrived, the hawk was quiet and enjoying dinner.

A woman whose finger got stuck in a drain was reported to be conscious and breathing.

Police responding to reports of a suspicious person hollering “ho-ho-ho” on Christmas Eve encountered a man in a Santa costume who makes a habit of going up and down the street greeting his neighbors every year.

A resident reported a large light in the sky. It was the moon.

But police blotters aren’t all fun and games, of course. Contrast these entries with those of another community just a few miles away, East Palo Alto. East Palo Alto, for several years in the ’80s and ’90s, was widely considered the most dangerous city in the United States. While the city’s crime levels have fallen in recent years, it still among the most unsafe places to live in the country:

A probation search of a 16-year-old gang member’s residence resulted in the seizure of a loaded semi-automatic handgun, a stolen shotgun, an assault rifle, numerous firearm ammunition magazines and cartridges of ammunition. The teen was also accused of threatening officers.

A joint investigation between the East Palo Alto and Menlo Park police departments led officers to an arsenal of weapons, including seven assault rifles, 10 handguns and more than 5,000 rounds of ammunition, in a storage unit. Two men were arrested.

A single police blotter may provide us little more than entertainment or strict information, when we compare two of them, particularly when they are from cities as different as Atherton and East Palo Alto, the juxtaposition highlights the gap between communities facing very, very different degrees of challenge when it comes to crime. And this brings to mind resources. With the two cities so close by, it’s hard not to wonder what would happen if the officer who responded to the call of a woman with her finger in a drain could have done more if he were instead patrolling in East Palo Alto.

Simone Seiver is Social Media Editor at Life of the Law.